Mapping "Portrait of the Mother as an Artist"

A digression on impression, legacy, motherhood, and art.

I’ve been thinking a lot about how the need to be impressive ruins writing—I’m not sure I can take this argument as far as its baseline of acknowledging an audience being ruinous, but in the rearrangement of my views as a pregnant human, my mind keeps questioning the idea of likability and impressibility. Do we need either to be writers out in the world?

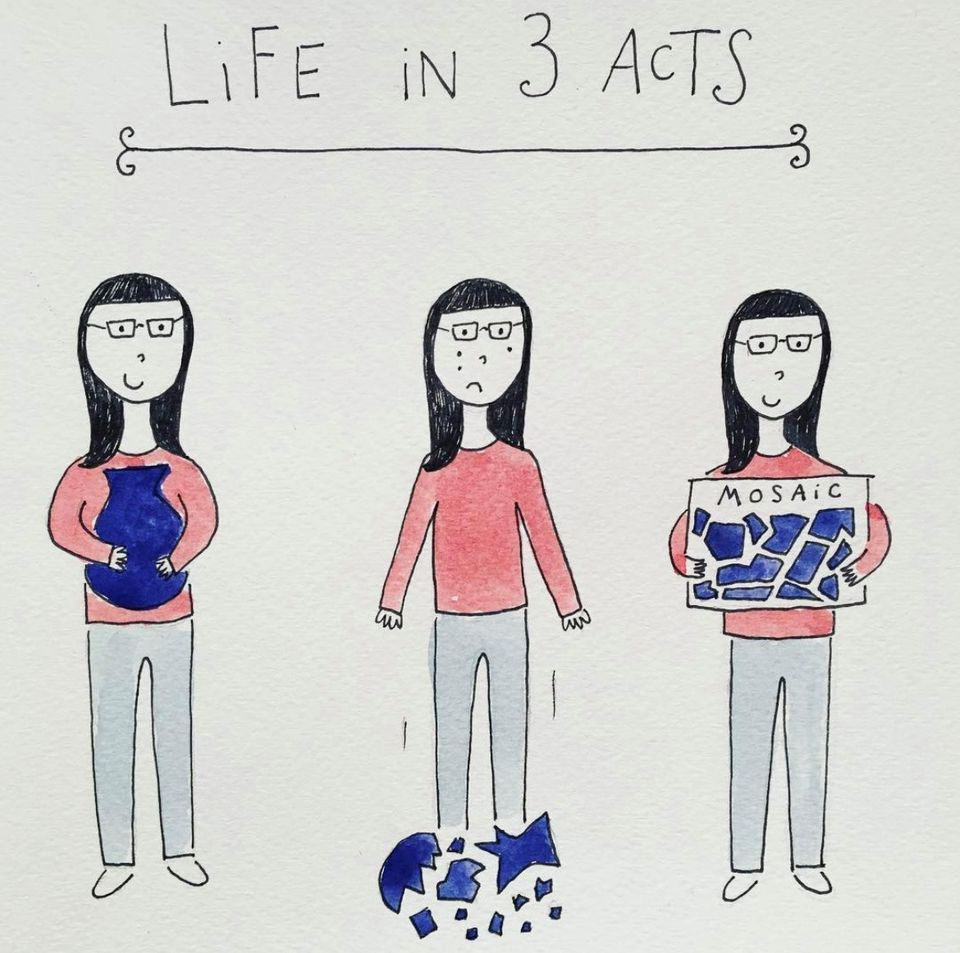

It’s why I haven’t looked at my MFA thesis in six months, or maybe never again. I wrote it with the dual focus of figuring out my girlhood and impressing my instructors. Neither which offered neat conclusions, though my defense trio told me in several different ways that I needed to tell a reader how to read it. It was a hybrid thing, where the past and the present were aligned differently on the page and speaking to one another, paired but without neat tracks. If it took any form it was the form of the mosaic—broken pieces placed intimately and intricately. It is art that will probably never be public.

So, with these questions in mind, I knew I had to tackle, “Portrait of the Mother as an Artist” by Rennie McDougall in Guernica. Sometimes I read essays until one starts attempting a question I’ve pocketed.

A brief note: It will be hard to follow this newsletter without having read the essay. Another brief note: this map and post have a lot of my own projections, not to be confused with McDougall’s essay being very worth reading.

Rennie McDougall is a writer based in Brooklyn, NY. His writing has appeared in T Magazine, The Village Voice, Lapham's Quarterly, Gay Magazine/Medium, frieze.com, Bookforum, Hyperallergic, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Brooklyn Rail, Slate, The Architect’s Newspaper, The Observer (UK), The Monthly (Aus) and The Lifted Brow (Aus), among others. His piece "Björk's Utopia" was awarded runner-up for The Observer/Anthony Burgess Prize for Arts Journalism in 2018.

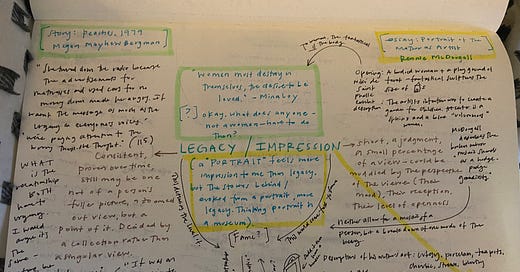

The full map:

When I opened McDougall’s essay in Guernica, the image immediately captivated me. It reminded me of the Minnie Evans Bottle Chapel at Airlie Gardens in Wilmington. Looking at it is like looking at a kaleidoscope, any degree you move you see something different. Evans started creating at forty-three after hearing a voice in a dream telling her to “draw or die.” After her death, artists, patrons, and leftover glass came together to create the bottle chapel in her honor.

I originally thought the question of McDougall’s essay was about compartmentalization and sacrifice—must we separate our several selves to have art that makes sense to an audience? But I think now, having mapped it, and like a fairy tale corvid collected strange bits from other things that have entered my reading and writing conscience, it’s about impression and legacy.

Reading How Strange a Season in the bathtub, the new collection from Megan Mayhew Bergman coming out in March, brought perspective to McDougall’s essay for me. I spent the soak reading her story, “Peaches, 1979.” I’ll start with the end, the epigraph to the next story is, “Women must destroy in themselves, the desire to be loved” — Mina Loy (from her Feminist Manifesto). Sometimes epigraphs are not the beginning of something, a way to enter, but the end of something—a simple lock, or maybe a bridge.

I am starting to think Loy’s sentiment is true for creating art in general. To get to the art in its truest form for you, what must be destroyed—and what arrangement of our lives must be made for that creation to begin, flourish, and then reach an audience? Arrangement is such a strange word to press on top of a life.

In McDougall’s essay, his mother’s art does come to readers, but it isn’t through the self, it’s through legacy. The title “Portrait of the Mother as Artist” makes me wonder if a portrait is more a piece of legacy or a piece of impression, which let me tell you, sent me on a rabbit hole.

“Portrait” feels more impression to me than legacy, but the stories behind / evoked from a portrait, seem to lean more legacy. I’m thinking about portraits in a museum. And why is this my question anyway? Well, because legacy seems consistent, proven over time, still isn’t quite a full picture, but a zoomed out view of one point of the full image. Legacy feels decided by a collection rather than a singular view. Impression feels short and quick, a judgment, a smaller percentage of a view that could be muddled by the perspective and openness of the viewer. Neither allow for a mosaic of a person, but a broken piece.

McDougall’s mother makes mosaic art, as do most of the women named throughout the essay. McDougall describes it as a “hodge lodge grandiosity”—she began creating this hodgepodge in her own house starting next to the doorway and then throughout the kitchen. Her art remains within domestic lines, and his description of it a few paragraphs into the essay backs that.

In “Peaches, 1979” Bergman describes the main character returning home after a long day, “It was an eight minute walk she could do in her sleep.” When I think about the walks I could do in my sleep, they’re all mapped by my knowledge of a place, my ability to retrace set pieces, knowing the mosaic—and any place I could perform this exercise is a domestic place.

Though some pieces loom larger in my mind, or through rehearsing the memory have changed, the domestic is the mosaic I know best. Last week I was telling my mom I wouldn’t take the jack-in-the-box bear from my childhood bedroom because it’s scary, and she said, “it’s a collector’s item.” Three years ago I described it in an essay with the phrase, “stiffened hair, cut off bowtie below the box, teddy as taxidermy.” I never played with him, but my brother sometimes pressed him into the darkness and rotated the wooden arm while a doll-jingle played and we waited for the bear to pop, but the bear—in my own impression of my bedroom, was a frightening menace. My mother repeated hours later, “it’s not scary.” I could walk the whole room from his perspective.

I don’t think this focus on the domestic as my most mapped place is because I’m a woman specifically, but because I was once a child like everyone, and most of my life has been set in domestic scenes. My impression of the world starts in the house of my body, and echos out from there to the house I’ve built with my chosen family, or the house I grew up in. A lot of my writing comes from my neighborhood, southern suburbia, but the larger the geographical area of the place, the less I know it. I think it’s because I have so many sense interactions with the domestic that my impression of the place has become legacy. A mix of fantastic and experience.

Prompt: What’s a place you could walk in your sleep? Walk it on the page.

My current conundrum though is that at what point, and at what expense, people (artists) are relegated to an impression, or depending on their level of publicity, legacy.

McDougall describes his mother as almost hiding from publicizing her art, “Not that she ever had any aspirations of fame.” (How does he know this for sure?)

In previous paragraphs to this, he describes her art in domestic and feminine terms, “cutesy, porcelain, tea pots, cherubic, strewn, bluntly cut daises” which made me think what’s the relationship between “fame” and the “domestic.” I guess it’s more a question of, what does a western society allow as a legacy from the domestic? I think of Toni Morrison, (the greatest), and how one of her strongest assets was bringing the world, both the uncanny and horrifying truth, into the domestic—whatever hauntings, whatever triumphs, whatever mud, whatever seeping, she let it in.

One of my favorite paragraphs of McDougall’s essay, he says, “To think of the mother as artist does not necessitate a conflict, nor does it require a choice between passive domestic surrender or total domestic rejection, although for a long time the world demanded that it did. Such frames only reinforce hierarchies, limit her to merely a fragment when, of course, she is composed of many pieces.” But both artists and mothers don’t seem to get this luxury of the mosaic—for me, it boils down to this question of impression or legacy.

Forgive me, because I want to fight this urge at every turn, but lately the force of the domestic has been strong on me as I continue to be pregnant, and look towards this idea of “motherhood.”

And I think I’m doing exactly what McDougall is telling his reader not to do, but I have to make the claim—although he wants the essay to reveal his mother as an artist, he continues to reinforce that she is a mother first. The mother, a sort of archetype. The pressure of this archetype, all it’s gnarled parts has weighed on me the last few months. There are so many ways to mother, but our stories feel limiting in their doling out of motherly roles.

The impression I walk away with as a reader is that she is mother then artist. That there is an order to the things we can be, the impression we make. This isn’t a bad thing, there isn’t conflict here, how can I possibly expect the son to separate the too, AND YET—I am so conflicted as a pregnant person about the perception the world will now place on me.

Every time I tweet about becoming a mother, I think, who is rolling their eyes? And this is my own internal conflict, my own drilled down perception of mothers that I want to fight, I know. (Cue internal misogyny).

The essay I’ve been working on for months about mushrooms and Godzilla and pregnancy is about the immediate change in impression and legacy having a child will make on my art—whether by my own doing, or the doing of those perceiving it—how my story and its worth will be tied to motherhood. I am scared, perhaps like everyone, about how I’ll be defined more than I ever have been before.

Halfway through McDougall’s essay he talks about how as a child, he and his sister enjoyed “fun house” photos of his mother where, “her eyes were caught unevenly mid-blink, or her mouth puckered … or she had a double chin, or the flash made her look like a big, glowing moon face.” He says, “she hated these photographs, found nothing funny in the accident of her momentary ugliness-made-permanent…”

I wonder if she hated these photos because they were not her (in her perception) or because they were a facet / impression of her that she did not like. One that even he claims could be permanently rendered. My fear of making art is maybe really a fear of perception, and then a fear of impression and legacy. So, a fear of control. When you let art into the world, you let go of its story—which is not necessarily your true story, but could be a grain in the mosaic chosen for your legacy. I fear that the grain in my mosaic will be mother before artist. I hate this fear.

Does McDougall’s mother not want him to write about her art because he could remember it wrong or because she knows his defining of her will say mother, rather than artist—his descriptions will be the legacy and the impression. His descriptions make her seen. Perhaps it’s not McDougall doing the separating, but me. I want to separate her selves, but is it our natural notion to then rank those selves? I think of Twitter bios that say something like, “mother, knitter, writer, not necessarily in that order.” But who decides the order—who can tell us what we are?

I think this is a question of how we define people we love, or people we hate, in our essays. I wonder how impression and legacy fall into this. What is the role of audience in that space. I tend to just write people in all their complications, and decide later if it’s worth attempting to publish.

But what’s the audience role in this? Does it matter if we’re given the space to create a breadth of work and those characters have space to change (closer to legacy), or if we are artists with limited publications, will our audience only ever get a limited story (closer to impression)? Is the pressure greater to find a “truth” or is the question much more about reaction from the person we put on the page, and our own turmoil over getting to the truth? I’m not sure, but I do feel like audience plays into it—and how we write about “real people” often doesn’t come up until we are facing an audience.

McDougall’s mother makes a Frida Kahlo sculpture and in the next paragraph he says that the sculpture is decorated in blue forget-me-knots. I want to know what his mother wants unforgotten. What this small floral gesture means to represent. McDougall says, “The Kahlo structure is distinct among Mum’s figures as a woman who is most definitely someone, not only because it is Frida Kahlo, but because the look in her face is heavy and vibrant with character; her psychology has been given sculptural form.”

Here are where things get weird. This morning I watched a TikTok about color vs. form. Color.Nerd makes the argument that “color is a litmus test for whether someone’s masculinity is toxic.” Basically, whether form or color is the most important thing in the arts—and often form is associated with masculinity and color with femininity. (This is a strange question for writers but I think it’s a how and why question—color as meaning, form as how meaning is arranged).

Four times in this essay McDougall paints out (get it, points out, I made the mistake and decided to keep it) women’s relationship to color. He describes Mirka Mora as working with a “limited color palette.” Then the new artist his mother has been following, Concetta Antico, being a “tetrachromat, a person who has four types of cone cells in their eye instead of three…and can see colors most people can not.” Though his mother points out that she doesn’t ‘use bright colors, but beige, bone’—colors that, to a normal eye, look uniformly dull ‘but obviously, she can see other color within that…a private visual world unrecognizable to others, but vibrant and lively to her.’

(If this isn’t a definition of the domestic, I don’t know what is—of the internal and private worlds of the home and the body as defined by those who could walk them in their sleep. “Unrecognizable to others” gives me chills—what legacy is made by those who can’t even recognize, metaphorically see the domestic, the body, the interior). How does one even attempt to write about pregnancy knowing this response?

Prompt: Try to define in only sense-driven prose a big ass idea or concept. Like, how—in a flash piece using only color, texture, metaphor, shape, sound, smell, taste, would you describe a concept. For some reason my brain is like, “do it with ‘the patriarchy.” But that sounds kind of awful, and kind of McSweeney’s.

Then, he describes his own aunt’s wardrobe after her divorce as full of color, “These choices were declarations of who she was, expressed through home and fashion loudly and unruly—unapologetically feminine. When Alison died, my mum, along with Alison’s daughter-in-law and granddaughter, performed a ritual of color by painting the coffin hot pink.”

Okay, I cried at this part. The women in his aunt’s life made her impression and legacy match (at her death) what she had already created as the perception she hoped to give out. But that’s not what made me cry. The next paragraph reveals Frida Kahlo’s private diaries (which she didn’t want shared), and McDougall describes as an “associative patchwork of words and sensations”—a mosaic—“no moon, sun, diamond hands—fingertip, dot, ray, gauze, sea. pine green, pink glass, eye, mine, eraser, mud, mother, I am coming - yellow love, fingers, useful child, flower, wish, artifice, resin.”

The impression of the associations for the reader are tinted by the colors Kahlo aligns them with. All of these women, his mother’s color wheel, using what’s closest to them to make, create, define, perceive, but not impress. Color as a means towards controlling perception without any need for perception at all. It exists, and they use it. Humans are unique in their reliance on sight as the dominant sense, but isn’t impression and legacy dependent on being seen. Dependent on viewing something from a specific degree, and refusing to walk around it another way—refusing to let in much complication, letting a dominant narrative overshadow other threads.

How do artists live in a world where they want to be seen and not be categorized, pigeon-holed, relegated? I am troubled. I want to be both, I want to be all, I want to be every piece in a smashed plate even if it’s rearranged into a new form by someone else. I want someone to cover me in forget-me-knots.

Craft—essay craft, tells me I can’t always have this. Though my writing is almost always described as “flowery” in workshop, though we are told to use containers, to have scope for our projects, to let only certain things in, to limit our thread counts, to focus essay questions towards an answer that is less messy for the reader, to think about our audience, to be perceived and leave an impression, to create a mosaic of work that will build a legacy—I want to clutter the narratives. My own, and the narratives of my art.

I want anything before public reception to be figuring, to be a hobby, to be a tinkering of associations without impression—I think we can all have this, until an audience wants claim, or we feel an audience’s perception on a piece. I am both writing a newsletter and want to take the audience out of the equation.

Any remedies for turning the idea of audience off? All I have is be like Gollum with your work until you’re ready to share it with any audience. It’s hard because sometimes you write a line and you’re like “oh, this is going to be the line people highlight” and then by the end of writing the thing, that line has to go. Can you do the cutting?

Is this why McDougall’s mother escaped the camera view when they spoke on the phone and he told her he wanted to write about her art? She is in a place of her own making—alone, but not lonely, creating without object definition, the permanence of anyone else’s viewpoint.

McDougall calls it “unfair” to call his mother’s art a “hobby,” which of course, makes me wonder why we take hobbies so much less seriously than art as profession, art as torture, art as dedication. As if hobbies aren’t steadfast enough. And that when he enters the bookstore, the clerk dismisses mosaics as a part of the “craft section.” He says, “Craft—a designation used to subjugate many art-making practices that have been the domain of women: needlepoint, pottery, quilt making. With their connections to the home, these mediums have been historically dismissed, supposedly lacking the rigor of complexity of high art.”

The questions about art here are astounding—and how answering these questions determines what art leaves an impression and what gets legacy: is the art ornamental or professional? public or private? (domestic?) color or form? made in the home or outside the home?

My question: is art just like history, left to those who write the story of its creation rather than the artist themselves? Becoming a mother has been a quarter tragedy for me—I am not the artist I wanted to be yet, I do not have a public book, I am not listed as the “greatest of…” anywhere, I am slow to create—taking a lot of stew time before I get to any conclusion neat enough for an audience. I feel behind even when my rational self tells me there is no race, no better timing.

I feel terrible calling motherhood a tragedy, but my mom asked me the other day if I finally came around to the idea of babies as miracles. That we can grow anything in a society that so badly wants to define and box it is a miracle to me—whether that’s a sculpture, or an essay, or a child. A society that defines the smallest parts of us, drills us down to micro plastics. A society that makes me feel like the definitions for “the mother” are limited to archetypes, when I know from real mothers, it’s as messy a thing as making art. It’s broken pieces strewn together: a study in revision, in churning, in attempt and question.

When the smashed teacup pieces of me are down—whatever destruction and creation I managed, I want to worry less about which piece broke bigger: mother or artist, and more about the associations made between them—how I was both and more.

Some interesting writing and creating on portraiture and art:

Mari Andrew’s most recent newsletter, Evolution of My Art (I love the focus here on audience and art)

Ann Patchett’s essay in Harper’s “The Portrait Gallery”

“Puddle”—a Visual Essay by Debbie Millman

Alexander Chee’s essay in Granta, “Portrait of My Father”

Sophia Stid’s INCH book from Bull City Press, Whistler’s Mother

Every Portrait Tells a Lie, blog by Debra Brehmer

Kim Pittaway in Brevity, “Here’s Looking at Me: Lessons in Memoir for Self-Portraiture”

“On Ashley Young and Chelsea Hodson” from Emily Labarge in The White Review

About Cassie Mannes Murray:

Cassie Mannes Murray is a literary agent at Howland Literary, where she started from the bottom with a cold email and a dream, and a publicist at Mindbuck Media. Before she weaseled her way into publishing, she produced a robust blog called Books & Bowel Movements, and taught public school. For writing, she has an MFA in creative nonfiction, has received a notable in Best American Essays 2020, and a Pushcart Prize nom. Her work has been featured in The Rumpus, Story Quarterly, Passages North, Hobart, Joyland, Slice Magazine, and Fugue. She’s married to a non-writing gamer, and they live with the fireflies in North Carolina where their dog chases street chickens.